At many clubs, Pulisic would be considered a once-in-a-generation prodigy but the German club have created something more valuable: a production line of once-in-a-generation prodigies, from Mario Götze, the wunderkind whose dramatic late goal for Germany won the 2014 World Cup final, to the fledgling France striker Ousmane Dembélé, who was bought by Barcelona last summer for €105m — an astonishing figure for a player who had started a mere 22 games for Dortmund.

With football’s January transfer window — a period in which teams can acquire players — in full swing, the continent’s best teams are sure to be circling around the German club’s best youngsters once more, desperate to grab the fruits of football’s ultimate finishing school. Those rivals may be better off asking themselves a key question: just how do Borussia Dortmund do it?

Night view of the Signal Iduna Park stadium, Dortmund’s home ground © Jasper Bastian

Residents of Dortmund

Night view of the Signal Iduna Park stadium, Dortmund’s home ground © Jasper Bastian

Residents of Dortmund, a blue-collar city in Germany’s Ruhr valley, say they feel civic pride about two things: erecting the world’s largest Christmas tree every year, and their vibrant football team. The feeling is summed up by the club’s slogan Echte Liebe, which means “true love”. It is a devotion shared by fans and club alike. The price of match-day tickets — and beer — at the team’s home ground Signal Iduna Park, known to fans as the Westfalenstadion, is kept low. The cheapest ticket is €16.70, the most expensive €54.40, a fraction of the cost at clubs such as Manchester United and Barcelona. Dortmund says they could charge more but that their duty to the city takes priority over making money.

In return, more than 80,000 fans regularly pack the ground, creating a memorably raucous atmosphere. After one recent match, the Real Madrid midfielder Toni Kroos told a Dortmund staffer that he was unable to keep his footing at corner kicks as the “yellow wall” of fans in the southern stand kept bouncing up and down, making the earth tremble.

It’s a philosophy that shapes Dortmund’s approach from top to bottom. All 200 players at the club, starting with boys aged eight, practise at the training ground in the quiet suburb of Brackel, where low-rise buildings are set alongside 18,000 square metres of manicured football pitches. The set-up is designed for the young players to see the first team up close, allowing them literally to view their path to the top. But the facilities are also deliberately sparse and unfussy — youngsters and veterans are encouraged to mingle on a level playing field.

The aim is to create a close-knit community, one that matches the club’s bond with the city it serves. The very best teenagers are invited to stay at Dortmund’s boarding school, with 22 boys aged between 15 and 19 housed in rooms at the training ground. The process can be brutal, too: the vast majority of apprentices will be cut from the club’s ranks over time, judged not good enough to play for the first team. Still, the club is proud that more than 50 players from their academy are currently playing professional football.

A session at the training centre in Brackel © Jasper Bastian

A session at the training centre in Brackel © Jasper Bastian

Out on the training ground, I am greeted by a man who wears a grey puffer jacket displaying the Dortmund crest but speaks with an English accent. Tim Kirk, 40, was hired by Dortmund earlier this year to coach their under-12s. A budding footballer as a child, Kirk’s own dream of turning professional ended following a serious knee injury aged 18. Instead, he went on to found a free coaching programme for local schoolchildren in Bath that produced 80 kids who moved on to the academies at professional clubs. It was a track record that brought him to Dortmund’s attention.

We try to find these extraordinary players when they are not at their peak. We develop them and then, at some time, we know that they will go

Michael Zorc, sporting director

Kirk tells me that at Dortmund his 12-year-old charges are not assessed on winning matches — that demand will come later in life — but on whether they reach a specific target. In a game, a striker may be told they will be judged not only on whether they score goals, likely to be one of their strengths, but also on how well they “press” or chase down a defender, potentially a weakness.

“It’s challenging them intellectually,” says Kirk. “I would say up to the under-12s, 70 per cent is technical, just getting them to become familiar with the ball and execute actions. As soon as you get into ages 12 to 15, you want them to start thinking two, three, four phases ahead in the game.”

Dortmund is the biggest club in the Ruhr region, and its youth team play against local sides desperate to beat their illustrious opponents in yellow and black. Wearing Dortmund’s famous jersey at an early age gives boys a sense of the burden they will feel as professional players at the club. As Lars Ricken, a one-time Dortmund teenage star who now leads the club’s youth system, tells me: “The 80,000 spectators at Signal Iduna Park want to see goals. It’s a kind of spectacle and we have to create such players who are willing to create chances, who are full of courage.”

Englishman Tim Kirk, hired by Dortmund to coach their under-12s team © Jasper Bastian

Kirk takes me to

Englishman Tim Kirk, hired by Dortmund to coach their under-12s team © Jasper Bastian

Kirk takes me to a single-storey building on the far edge of Dortmund’s training ground. Inside lies the Footbonaut, a machine that has played a key part in the club’s methods. He smiles as he sends me into a robotic cage in the shape of a cube, and a floor laid with a pitch made of artificial turf. Each of the four walls is also made up of 16 square panels and, when the machine starts, balls fly at me from different angles and at different speeds, seemingly at random. Buzzers and flashing lights provide a split-second clue as to where a ball is coming from. My task is to trap the ball using my body, then strike it into one of the panels that lights up as a target. It is the footballing version of Whak-A-Mole. And far beyond my capabilities. At one point, I spin around to have a projectile fired into my thigh, almost knocking me over. Kirk is clearly amused.

The Footbonaut is hardly a secret weapon. Invented by the Berlin-based designer Christian Güttler, Dortmund installed it in 2011 at a reported cost of about $3.5m. But since then, only one other German club, Hoffenheim, have paid to build one. It may be no coincidence that, over the past decade, Hoffenheim are the only club in the Bundesliga to have regularly featured a younger starting 11 than Dortmund. Why, I ask, hasn’t every team installed this machine? “It’s expensive,” says Kirk. “I think clubs would rather invest money in things that give them an immediate return.”

I think they saw a lot of what I do now, my attacking mode, or just being a creative player and making a difference in the game

Christian Pulisic

The Footbonaut is not used by first-team players, already good enough to have mastered it. Instead, weekly sessions are provided for the younger players with the aim of giving each boy 5,000 extra “ball contacts” a year. Coaches tell me Christian Pulisic “lived” at the centre when he first arrived at Dortmund. But, they add, its greatest disciple was Mario Götze, who developed the ability to control balls fired at 100kph — double the velocity I faced.

The Footbonaut may even have won Germany the World Cup. As Raphael Honigstein explains in

Das Reboot, his excellent book on German football’s quest for reinvention, the 2014 final between Germany and Argentina was goalless and heading towards the end of extra time, when, in the 113th minute, a high ball was delivered to Götze, on as a late substitute. In one sweeping movement, he chested the ball forward, then volleyed it into the corner of the net. It was a manoeuvre he had completed thousands of times before inside the Footbonaut.

[video]

https://youtu.be/WhAyX81zP2M[/video]

“By the time they get to Götze’s level, everything they do is pretty much automatic, because they’ve just honed it, they’ve trained it,” Kirk explains. “It’s all about pictures. At a young age, you’ve just got to build and give them as many pictures about the game as possible so that they can choose the right one when the time comes.”

I ask him whether Dortmund’s young charges benefit from the “10,000-hour rule”, the popular idea that the key to achieving world-class ability is to spend that length of time practising a particular skill. “You’ve got to be careful with 10,000 hours,” Kirk warns. “Because it’s not just the 10,000 hours itself, it’s the content and it’s the manner in which the 10,000 hours are done. It’s about purposeful practice.”

The coach is referring to the work of Anders Ericsson, a Swedish psychologist dubbed the “world’s reigning expert in expertise” who argues that mindless, rote repetition should be carefully distinguished from focused, “purposeful practice”.

This requires certain conditions to be met, making students go beyond their “comfort zone” by constantly attempting skills just outside their current ability. It’s a kind of practice that allows true experts to create superior “mental representations” — that is, accurate pictures in their mind of how to perform their extraordinary tasks. An Olympic diver visualises the correct body positioning as they somersault through the air.

A chess grandmaster sifts through a staggering array of future moves, before picking the best one.

With their emphasis on youth and continuous development, Dortmund are a temple to such purposeful practice. To better understand the effect that years of dedicated training can have, I speak to Marco Reus, the Dortmund-born winger who is one of Germany’s most recognisable players.

“When I do get the ball, it’s already too late to start thinking about what to do,” says the 28-year-old, when we meet in the bare Portakabin in which the club holds its press conferences. “I try to play in such a way that, when I get the ball, I already automatically know what will happen next.”

Marco Reus, Dortmund-born winger and German international © Jasper Bastian

Marco Reus, Dortmund-born winger and German international © Jasper Bastian

To illustrate his point, he recalls a recent Champions League game against Real Madrid. With Dortmund 2-1 down, Reus’s teammate Emre Mor slides a long pass down the right side of the pitch, past Madrid’s centre back Sergio Ramos, into the path of striker Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang. “You know a situation may arise . . . and then,” Reus clicks his fingers, “one second earlier, or not even that, you need to start your move earlier than your opponent. I know Aubameyang is faster than Ramos, so I try to start off earlier than my defender to get ahead of him.”

Reus is sprinting towards goal, a yard ahead of Madrid’s chasing players. Aubameyang crosses the ball low. Reus slides just in time to meet the ball with his left foot, caressing it over the onrushing goalkeeper. He runs over to Aubameyang and the pair waggle index fingers at each other as if to say: “I knew you were going to do that.” Reus says his body simply reacted to a premonition that appeared a few seconds earlier: “And that’s how it played out.”

Borussia Dortmund fans and players celebrate winning the Bundesliga title, May 2011 © Getty

In March 2005, about

Borussia Dortmund fans and players celebrate winning the Bundesliga title, May 2011 © Getty

In March 2005, about 450 investors in Borussia Dortmund met in a building at Düsseldorf airport. A Dortmund executive told them the club would be declared bankrupt unless they signed up to a bailout plan. The proposal was accepted. Later it emerged that one outside group that helped save the club was their arch-rival Bayern Munich [Germany’s richest and most successful club], which had loaned €2m.

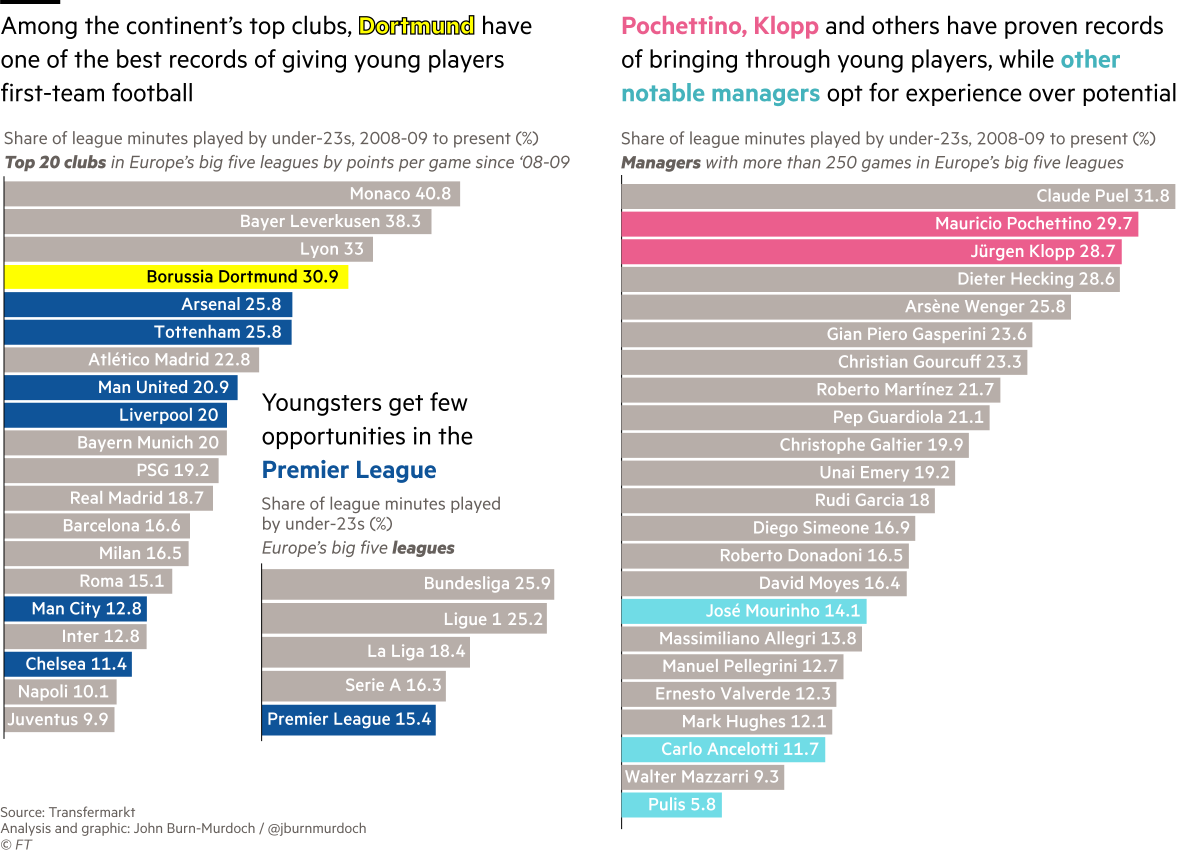

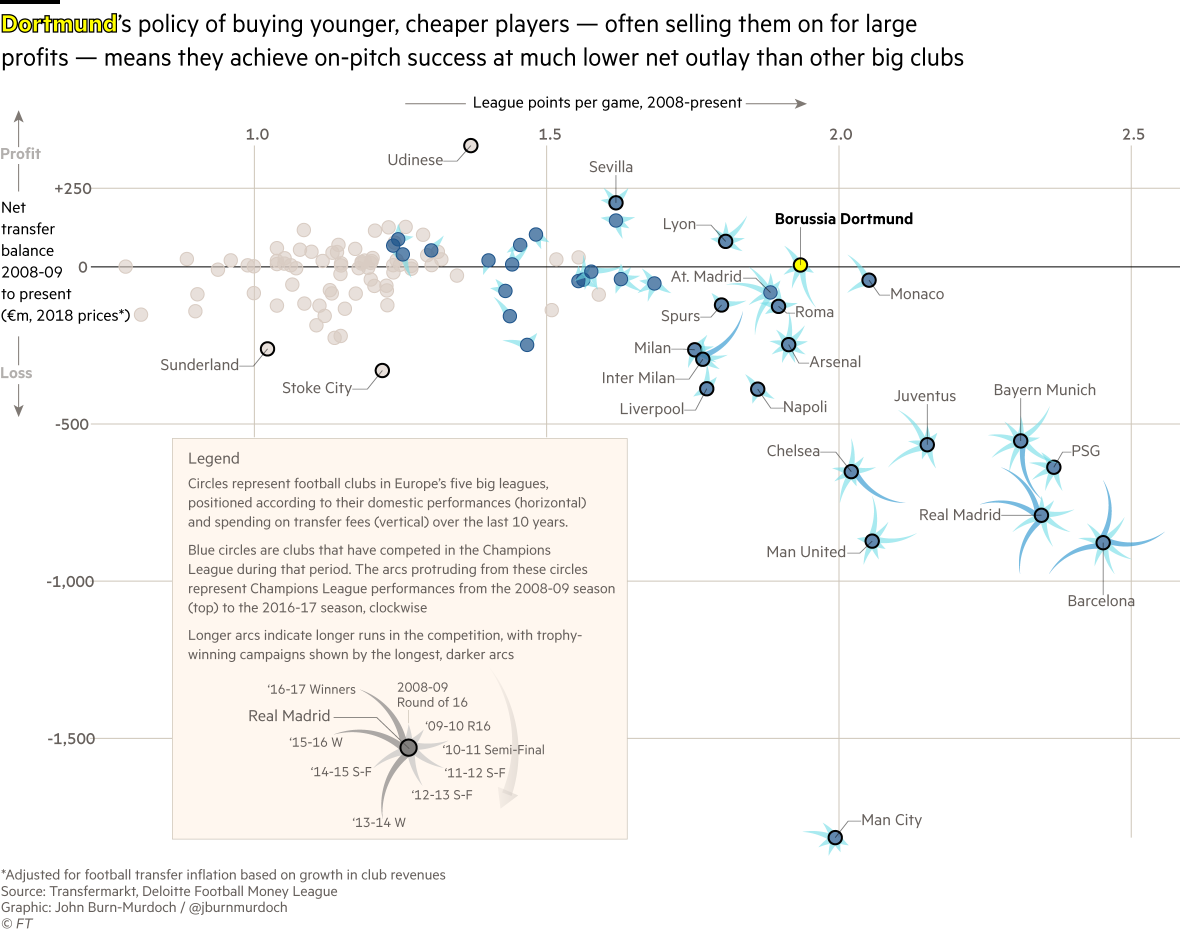

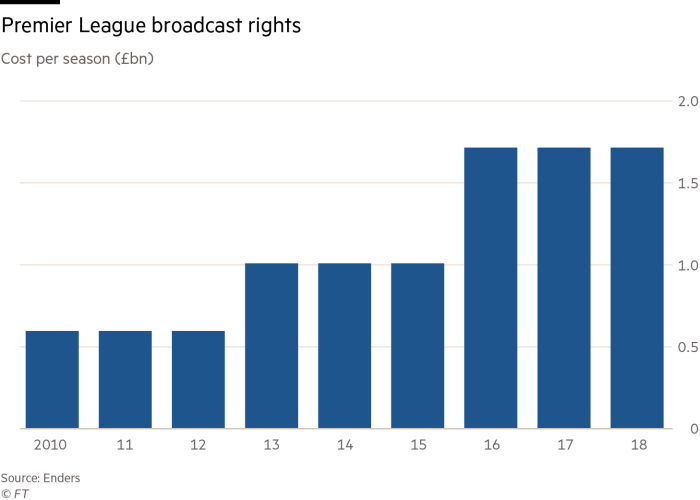

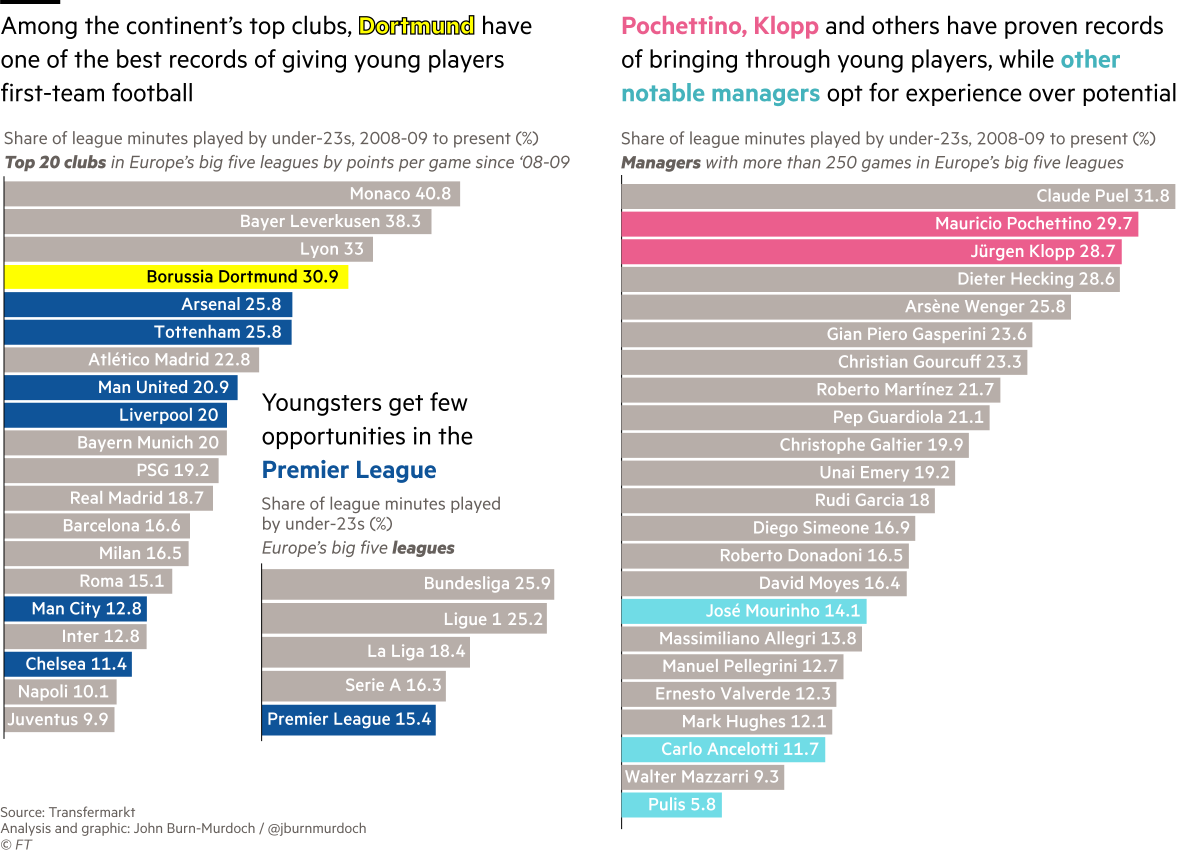

Academic research has shown that, in football, money does buy success. The best indicator of a club’s league position is a club’s wage bill. The problem was Dortmund didn’t have the cash to buy success. In trying to do so they had overextended themselves by paying huge salaries to star players.

Carsten Cramer, Dortmund’s chief operating officer, summarises the club’s financial crisis during this period succinctly. “We tried to overtake Bayern Munich, although we should know that it will be never possible to overtake a Bayern Munich.” Even today, when Dortmund rank as the 11th richest club in the world, with revenues of €283.9m in 2015-16 according to Deloitte, they remain far behind Europe’s true super clubs such as Bayern, which had annual revenues of €592m over the same year.

Michael Zorc, Dortmund’s sporting director © Jasper Bastian

Michael Zorc, Dortmund’s sporting director © Jasper Bastian

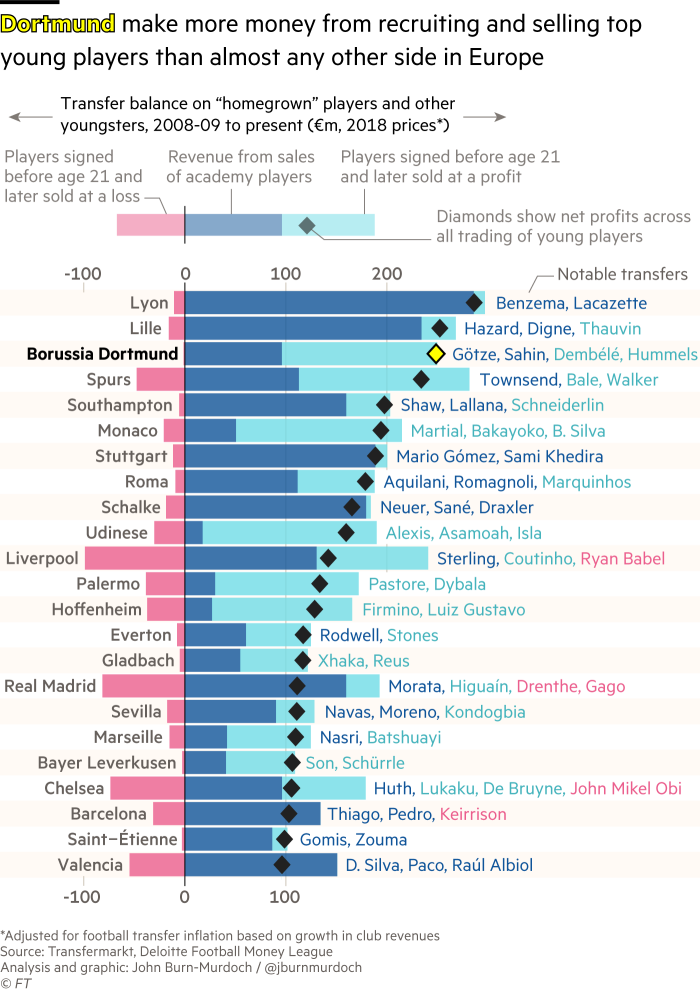

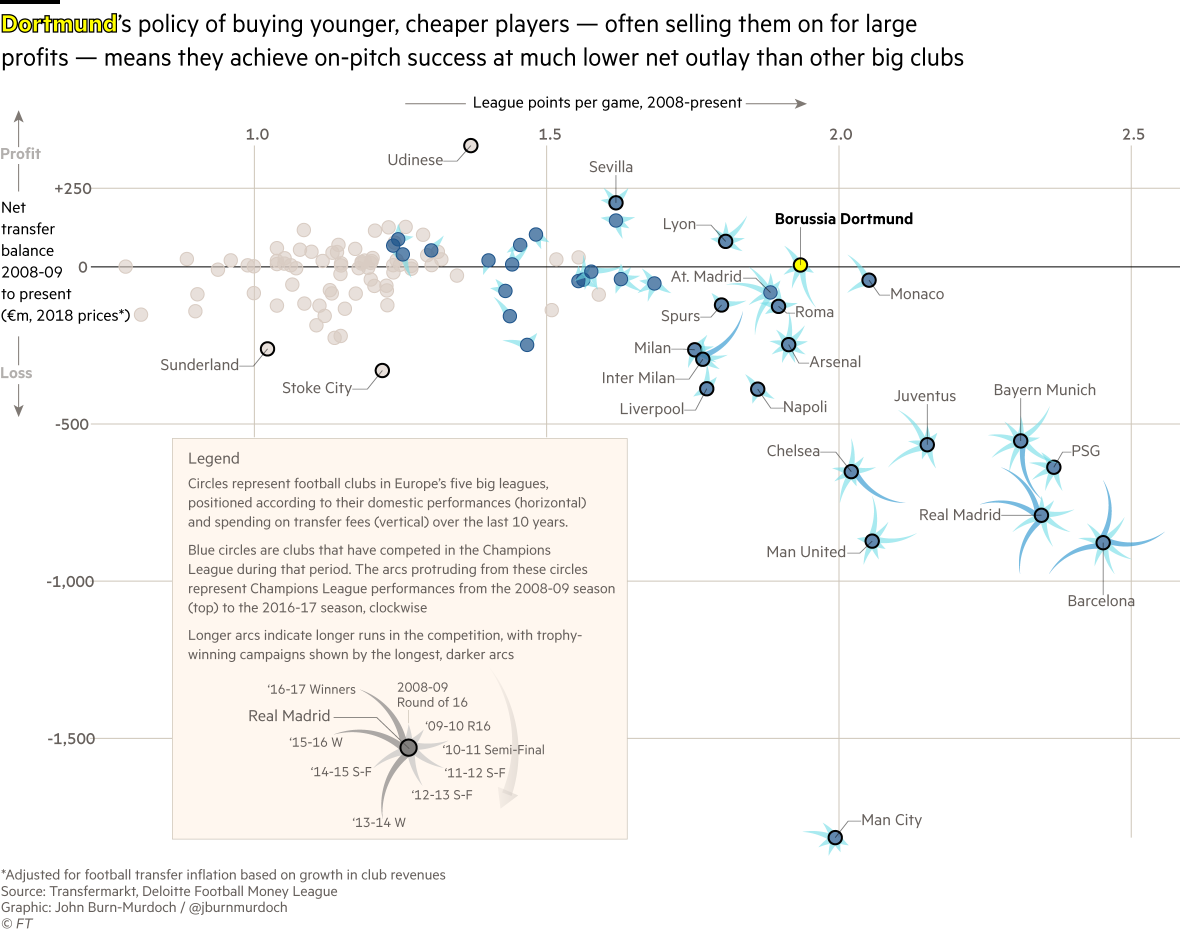

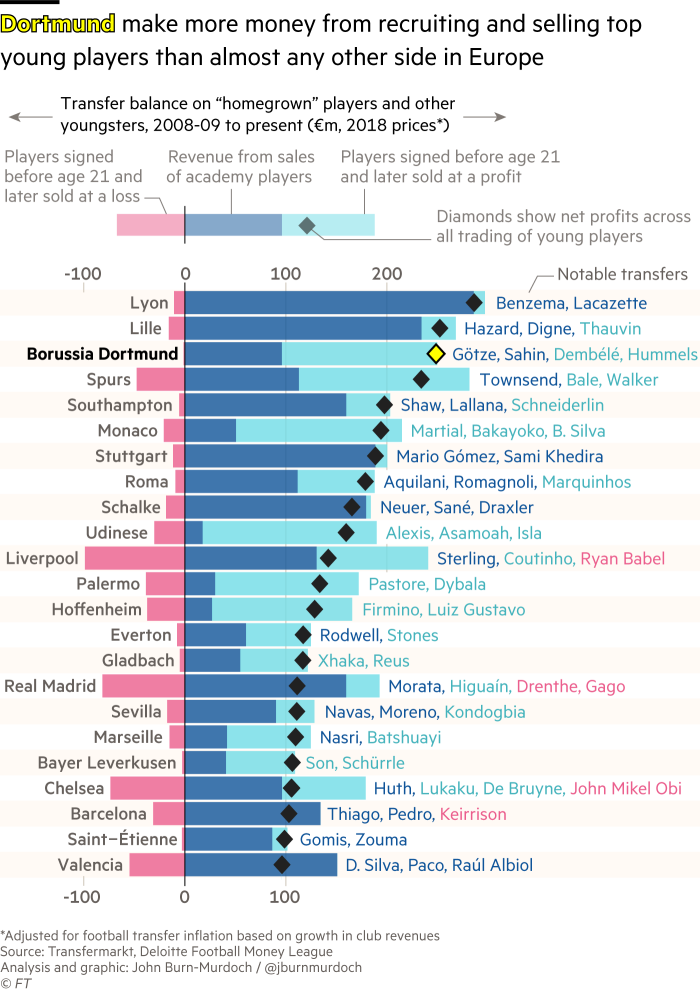

Dortmund’s solution to bridging this gap was to invest in cheaper, younger players. They sought to develop local kids through their academy system. Reus and Götze joined the club as boys, as did others who became Germany internationals, such as Kevin Grosskreutz and Marcel Schmelzer. The club also scoured the globe for youngsters such as Shinji Kagawa from Japan and the Gabonese striker Aubameyang, often thrusting them straight into the team.

The plan paid off under legendary former coach Jürgen Klopp. When Dortmund won back-to-back Bundesliga titles in 2011 and 2012, the average age of his first title-winning team was 23.3 years, among the very lowest of the more than 100 clubs that have played across the “Big Five” European leagues of England, Germany, Spain, Italy and France over the past decade. Klopp had designed the perfect system for his youngsters — built on manic efforts to win back possession of the ball immediately after losing it, then streaming forward en masse to overwhelm the opposition. He later described it as “heavy-metal football”.

Yet Dortmund’s success quickly attracted attention from Europe’s biggest spenders. As the players evolved into superstars, some came to expect superstar wages. Instead of paying more to keep them, Dortmund decided to sell to rivals who would. Götze went to Bayern Munich for €37m in 2013. Over the next few seasons, Bayern picked off two more key Dortmund players, Robert Lewandowski and Mats Hummels. In 2016, Götze’s replacement Henrikh Mkhitaryan was sold to Manchester United for €42m and United’s neighbours Manchester City bought Ilkay Gündogan for €27m.

Zorc insists this is not a business strategy and Dortmund would rather keep their best players. It is, rather, an acceptance of economic reality. “It’s because of money that is in the [English Premier League] and in these two clubs in Spain [Barcelona and Real Madrid]. By knowing this, we try to find these extraordinary players when they are not at their peak. We develop them and then, at some time, we know that they will go, like Gündogan to Manchester City; Sahin to Real Madrid; now Dembélé to Barcelona.”

The corollary is that Europe’s brightest prospects continue to be drawn to Dortmund. Last summer, Alexander Isak, a 17-year-old Swede, received an offer to join Real Madrid. Most would find it hard to turn down the chance to join a club that have won back-to-back Champions Leagues and feature superstars such as Cristiano Ronaldo and Gareth Bale. But when Dortmund made a last-minute counter offer, Isak did just that.

Alexander Isak, 18, who turned down a Real Madrid offer to sign for Dortmund © Jasper Bastian

Alexander Isak, 18, who turned down a Real Madrid offer to sign for Dortmund © Jasper Bastian

He jokes that he chose Dortmund over Madrid because of “the simple beauty of the city”. But when I press him, he says: “I know the club and they achieved a lot with young talent and that makes people think that it is a good place. Real Madrid is probably also a great place for a challenge but Dortmund just felt right for me.” Isak made his first Bundesliga start last weekend.

For Cramer, the most important lesson of the club’s financial crisis in 2005 was “to focus on yourself, ask yourself what you stand for”. As a result, there is an acceptance that “we will be able, sometimes, to make it a little bit more difficult for [the likes of Bayern Munich and Manchester United], but it’s not part of our DNA to be obligated to be number one.”

If there is a concern, it is that Dortmund have become victims of their success, unable to keep hold of their best footballers for long enough to produce a winning team. Dembélé was there for just a year after the German club hired him as just another budding prospect for a fee of only €15m. In November, Sven Mislintat, the club’s chief scout who helped to discover many of their recent stars, joined Arsenal.

Speculation now centres on the slight figure of Pulisic, who I meet in a cafeteria after a training session. He enters the room wearing a hooded blue jacket, appropriate for a freezing day in which drizzle threatens to solidify, and tackles my questions gamely but with caution.

[video]

https://youtu.be/jOYod2pJ4mY[/video]

Pulisic says he doesn’t remember much about his performances in Turkey that impressed Dortmund’s scout, though “I think they saw a lot of what I do now, my attacking mode, or just being a creative player and making a difference in the game.” But he credits his subsequent emergence as one of the world’s best young players to Dortmund’s willingness to thrust him into the first team far earlier than most clubs would have contemplated.

The player bats away the suggestion he is in line for a lucrative move elsewhere. “I’m not trying to impress another team,” he says. “I’m doing everything I can to help my team here.” Yet, few believe that if Pulisic continues on an upward trajectory he will stay beyond a few more seasons.

Almost inevitably, it seems, a further stage is built into Dortmund’s process of continuous improvement; the chance to move to a megaclub like Barcelona and Real Madrid, where the standard of teammates — and the competition for places within the team — will be even higher.

Unusually, the Dortmund way means it’s an outcome that could satisfy both player and club. “I learnt how to be a true professional and I was able to take a bigger step,” he says. “[Dortmund] always gave me opportunity. They allowed me to play, they gave me the training with the first team. They allowed me to develop, not too fast, but in the right way.”

Murad Ahmed is the FT’s leisure correspondent

https://www.ft.com/content/da604a8c-fb1 ... 9be7f3120a