Manchester City and the ‘Disneyfication’ of football

Team’s owners are developing a global network of clubs that could transform the sport

Even diehard football fans would struggle to identify Yangel Herrera. Yet if Manchester City’s billionaire owners are correct, the Venezuelan midfielder could be the first proof that its global business model is paying off.

The 19-year-old plays for sister club New York City, a US team founded four years ago as part of the City Football Group, an umbrella organisation stretching from Australia to Japan, Spain, Uruguay, the UK and US. It is a franchise model dubbed by some as the “Disneyfication” of football and which its Arab owners believe is the future of the world’s most popular sport.

Mr Herrera’s place in that plan is yet to come to fruition. While he will not play in Sunday’s Manchester derby, pitting City against their neighbours United in a match expected to attract a worldwide television audience of hundreds of millions, he is one of an estimated 1,000 players CFG clubs can draw on — a reservoir of talent that stretches from academies to the first team.

Signed in June from Atlético Venezuela in Caracas for an undisclosed fee, Mr Herrera was identified using the group’s industrial-scale database of 300,000 players. Manchester City immediately loaned him to New York City where coach Patrick Vieira was searching for a dynamic player to add to his Major League Soccer side. If all goes to plan, Mr Herrera may next play in Manchester. He would then become the stand out figure in a grand footballing project aiming to upend the football industry.

Players need time to develop” says Mr Vieira, the former Arsenal and France player. “If Yangel Herrera manages to play for Manchester City . . . that would be exciting for us.”

CFG says its ambition is to build the “first truly global football organisation” and its owners are at the vanguard of a growing trend for wealthy individuals to control multiple clubs. The intention is for each of the teams in the network to be profitable in their own right, but co-operate to identify and train the world’s best players, while securing marketing deals to fund the wages of footballing superstars.

At its heart is Manchester City, bought in 2008 by Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed al-Nahyan, the billionaire businessman, deputy prime minister of the United Arab Emirates and member of the Gulf state’s royal family. He promised to transform the team — which had spent decades in the shadow of its more successful city rival Manchester United — into a global megaclub capable of winning Europe’s biggest prizes.

At the time such ambition was ridiculed by United’s then manager Sir Alex Ferguson, who described it as the excitable talk of “noisy neighbours”. Back then, it was United that provided the blueprint for success, both on and off the pitch, winning 13 Premier League titles and two Uefa Champions Leagues in the Ferguson era — a period in which it pursued international sponsorship and marketing deals. It remains the world’s wealthiest club in terms of revenues, €689m in 2015-16, according to Deloitte. By comparison, Manchester City revenues over the same period were €525m.

In reality Sheikh Mansour’s estimated personal wealth of $20bn, from holdings in Abu Dhabi’s oil and gas entities, give the club greater financial resources than all its rivals. His largesse helped City overtake United on the field, spending £200m a year on transfers and wages, incurring several seasons of heavy losses but winning two Premier League titles in 2012 and 2014. It also attracted investors, with the China Media Capital consortium paying $400m for a 13 per cent stake in CFG in 2015, valuing the group at more than $3bn.

In recent years, the Emirati prince has funded a different spending spree. In 2013, Manchester City joined with the New York Yankees to pay $100m for the franchise rights to create a football team in New York. CFG then struck smaller multimillion-dollar deals to buy Australia’s Melbourne Heart, since renamed Melbourne City, and Uruguay’s Club Atlético Torque. It also acquired minority stakes in Yokohama Marinos in Japan and Spain’s Girona.

Other groups and individuals are now seeking to emulate the model of multi-club ownership. Red Bull owns football clubs in the US, Austria, Germany and Brazil, partly as a way to promote its energy drinks. But few can match CFG’s ambition, which has already seen it expand across four continents. The group is also evaluating takeovers in China, India and Southeast Asia.

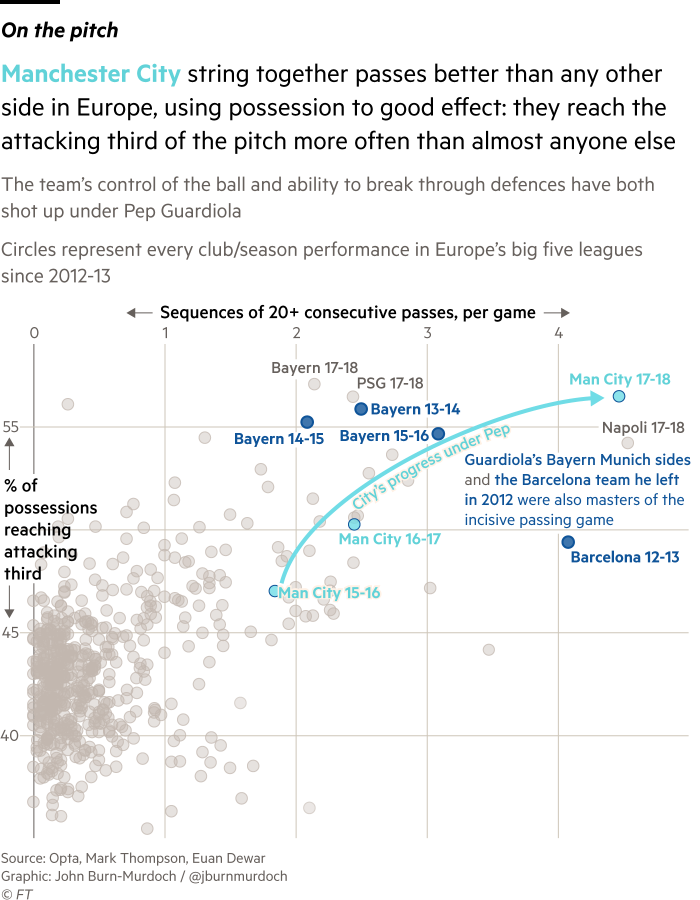

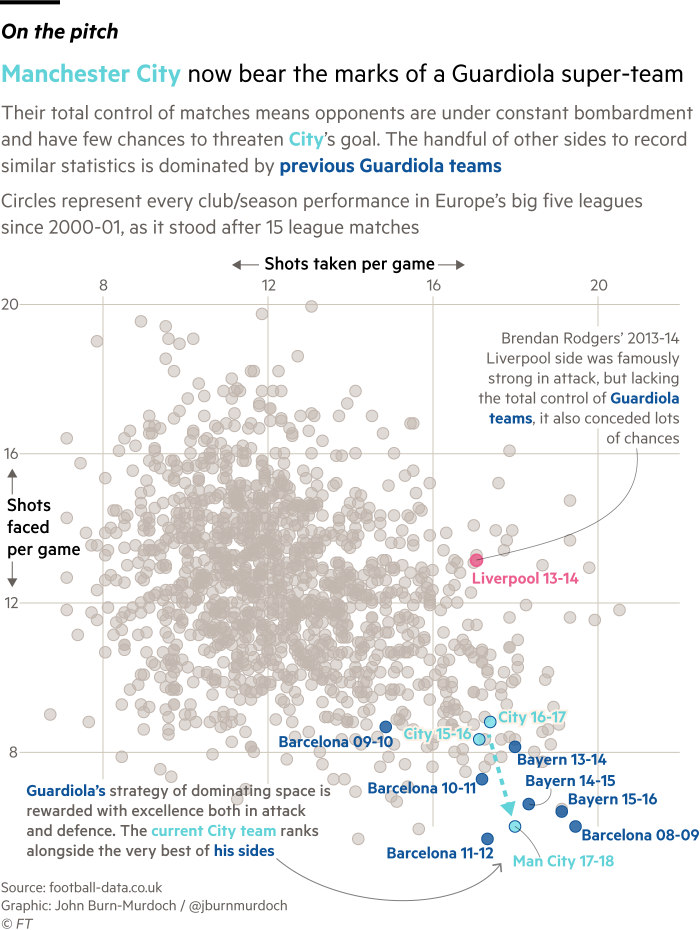

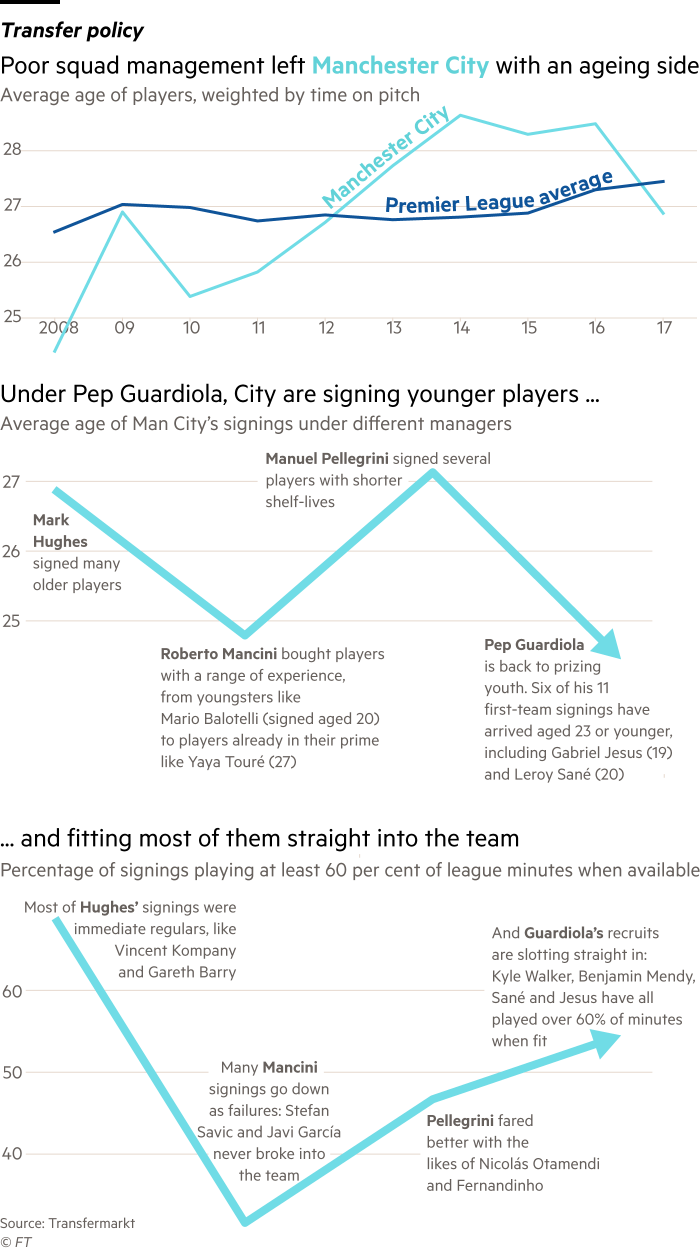

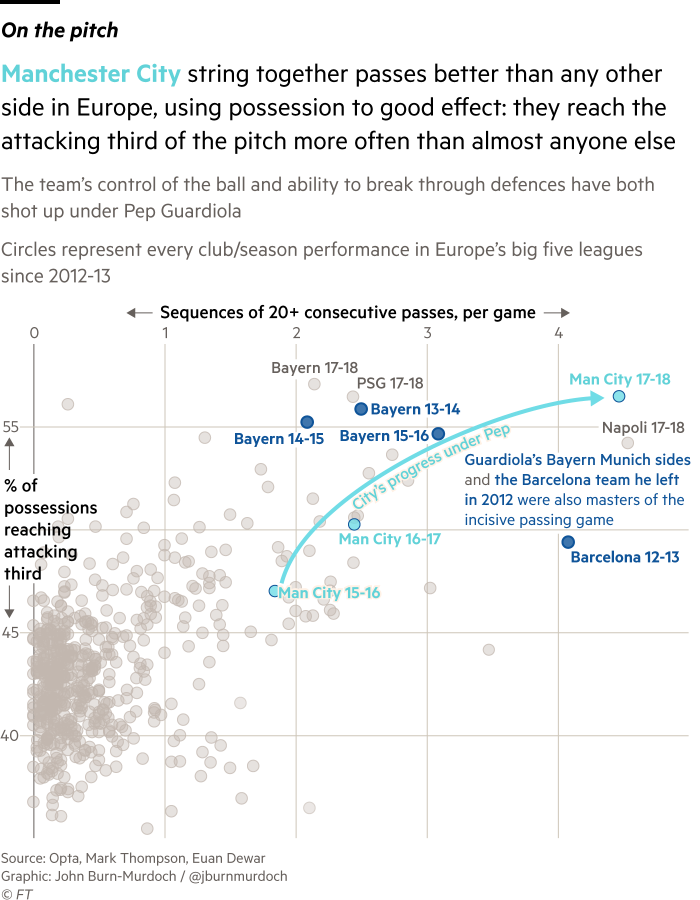

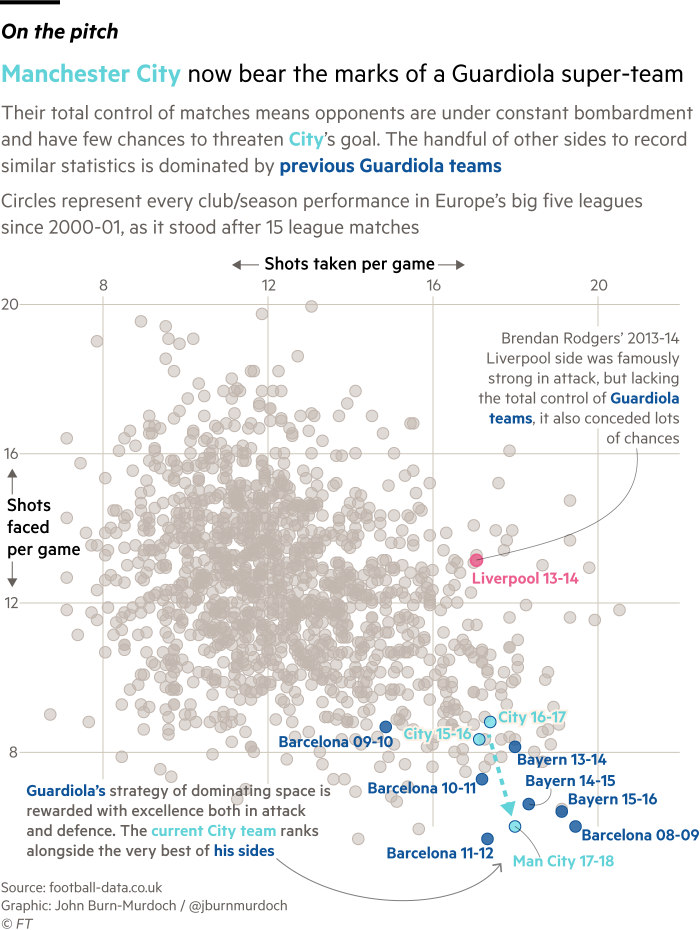

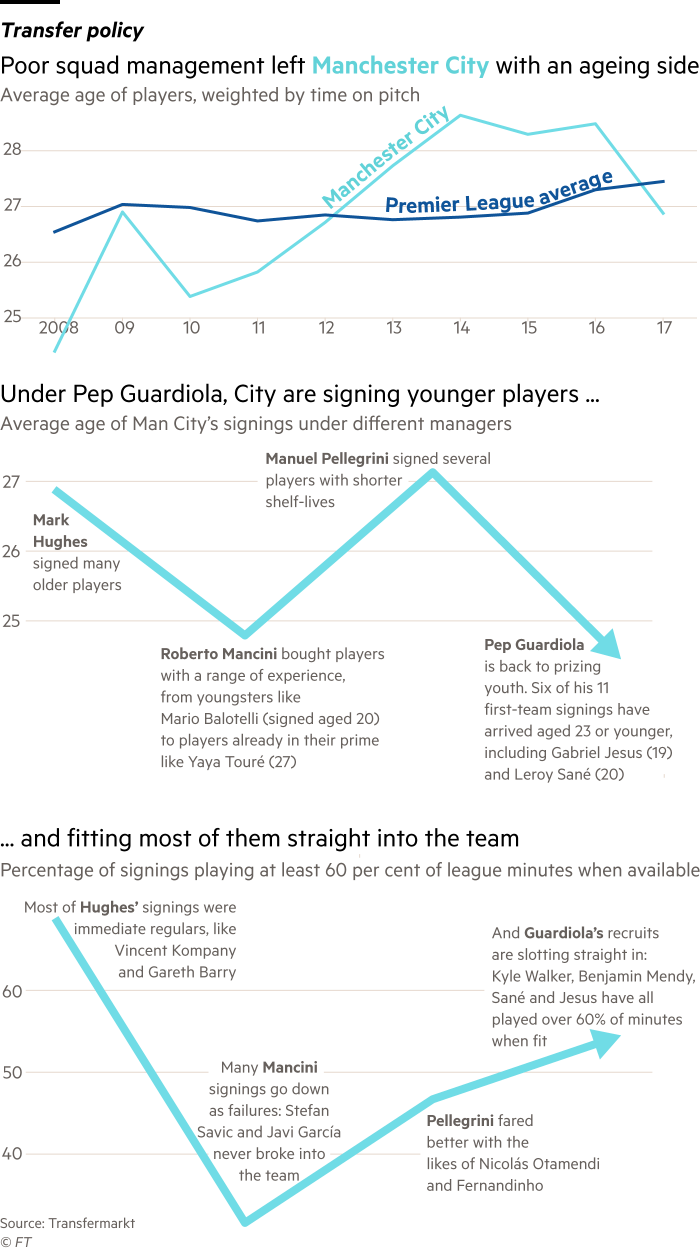

CFG executives say the goal on the pitch is for all the clubs to play attacking, possession-based football, in the style laid down by City’s head coach Pep Guardiola, who was previously at the Spanish club Barcelona. They also want to outdo United’s balance sheet, by exploiting “economies of scale” by convincing sponsors to pay for marketing deals that apply across its teams.

Critics argue the elaborate business model is a smokescreen to satisfy Europe’s so-called Financial Fair Play rules, introduced in 2011, designed to prevent individual clubs from spending beyond their means to buy success.

A senior Premier League club executive describes CFG as a “hall of mirrors” designed to funnel revenues back to the central entity in Manchester and justify its enormous spending on players. A £400m 10-year deal with Etihad, Abu Dhabi’s state airline, to become Manchester City’s stadium and shirt sponsor, led to accusations of “financial doping” by Andrea Agnelli, president of Italy’s Juventus. The group admits that Manchester City, which benefits from the Premier League’s multibillion-pound TV contract, is the only profitable club in its network.

Others suggest CFG represents a geopolitical play, designed to exert Emirati soft power by creating winning teams in the world’s favourite sport. One Premier League club owner refers to Manchester City as “the nation state” playing an entirely different game to its rivals.

“Abu Dhabi is not doing this because it likes Levenshulme [a district of Manchester],” says Simon Chadwick, professor of sports enterprise at Salford Business School. “They are doing this to seek sustainable revenue streams from the investments that will provide currency inflows in 10, 20, 50 years’ time when the oil and gas is gone.”

The origins of the CFG network lie not in Manchester or Abu Dhabi, but Barcelona. In 2003 Ferran Soriano, a management consultant, was elected to the board of the Spanish football club and set about transforming the institution. In his book Goal: The Ball Doesn’t Go In By Chance, Mr Soriano says he was influenced by the work of sports academic Stefan Szymanski, which showed that the best predictor of a club’s success was the wage bill of its playing squad.

“If you want a champion team, a team with a chance of regularly winning championships, then you need to work consistently to have a big club that generates enough revenues to be able to sign the best football talent available,” wrote Mr Soriano. “It has absolutely nothing whatsoever to do with luck.”

Fearing being outspent by richer clubs such as Real Madrid and Manchester United, Barcelona pushed to reach financial parity. Between 2003 and 2008, it almost trebled revenues from €123m to €309m and cut the gap to its rivals. On the pitch, too, it has been successful, winning four Champions League titles since 2006.

Mr Soriano was following a commercial model first adopted by Manchester United: increase match-day ticket prices, seek sponsorship deals outside its home market and go on the road for pre-season exhibition tours of North America and Asia. But he wanted to go further, pointing to the franchise model of Walt Disney — which translates movies into different languages, creates merchandising around characters and film-related theme park rides — and suggested a similar formula could be applied to sport.

Mr Chadwick describes the idea as the Disneyfication of football. “You can’t take the first 11 to America one week, China next week, South Africa the next,” he says. “So what you do is franchise the name, sponsors, kit and image.”

Barcelona’s leadership rejected the Soriano idea to launch international sister clubs, and he left the club in 2008. Four years later he joined Manchester City as chief executive. “The week after Ferran joined he was already in New York speaking to Don Garber [commissioner of Major League Soccer],” says Omar Berrada, a former Barcelona executive who now works alongside Mr Soriano as Manchester City’s chief operating officer.

CFG believes the network allows City to spread its brand by attracting local supporters to each of its clubs while also adding to the value of commercial deals, in ways unavailable to even the biggest European clubs. Tom Glick, Manchester City’s chief commercial officer, points to the example of carmaker Nissan, the majority owner of the Yokohama Marinos. In 2014, CFG took a 20 per cent stake in the Japanese club. Nissan subsequently struck a deal worth more than £20m as a sponsor of all the CFG clubs.

They also argue that the group structure helps to spot players and place them within the network. Investments in clubs such as Girona, and a partnership with NAC Breda in the Netherlands, are designed to create finishing schools for young starlets.

“We have 10 players within our system that are getting experience in the Eredivisie [the Dutch top division] or La Liga [Spain’s top league],” says Brian Marwood, the ex-Arsenal player who heads CFG’s global scouting operation of 50 talent spotters on five continents. “That is invaluable.”

Yet when table-topping Manchester City — which is seeking a 14th straight win in the Premiership — face United on Sunday, its team will be made up of expensive imports rather than young players developed within the CFG network.

Executives plead for patience, saying the system has already created a new revenue stream. One example is Aaron Mooy, an Australian who played for Melbourne City and has since moved to Huddersfield Town in the Premier League. According to people close to the club, Mr Mooy’s transfer fee of about £10m was more than the price CFG paid to acquire the Australian club.

Still, Professor Szymanski, whose work influenced Mr Soriano, doubts the business model. Neither notoriously parochial fans, nor commercial sponsors, will care if a club is part of a larger brand, he says. He adds that there is only “marginal benefit” in running a whole club compared with opening cheaper youth academies in multiple locations. Worse, he fears CFG risks “managerial overstretch” by trying to run several clubs, rather than focusing attention on one.

Prof Szymanski advises other club owners to bet on Manchester United’s business model, rather than the “riskier” one of CFG. But he adds a caveat: “When you have a bank like Sheikh Mansour to draw on, why wouldn’t you? If you are in Soriano’s position, what’s to lose? You’re betting with someone else’s money . . . he might hit the jackpot.”

How CFG is extending its reach

The CFG web of clubs is set to grow. The 2015 purchase of a 13 per cent stake in the group by China Media Capital was seen as a prelude to acquiring a club in the country.

Omar Berrada, Manchester City’s chief operating officer, says CFG has been quoted “crazy valuations” for clubs in the China Super League, the country’s top division, and asked to pay hundreds of millions of dollars to acquire clubs that were unprofitable and under heavy debt. “Clearly, we’re not going to make a crazy investment,” he says.

Without ruling out buying a club in China, CFG says other efforts, such as creating football schools to train young players, a key goal of the Chinese government, makes “more economic sense”.

India is another option, but CFG is yet to find a commercial partner, as with the Yankees in New York and Nissan in Yokohama, to navigate the Indian market. Mr Berrada lists Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia and Malaysia as other potential territories for growth.

The model could yet be tested by the sport’s authorities. In August, CFG acquired a major stake in the Spanish club Girona, alongside an investment vehicle controlled by Pere Guardiola, football agent and brother to Manchester City’s head coach. “It’s definitely not to keep Pep here,” says Mr Berrada of the Girona deal. “It’s not any sort of a hook to keep him interested in the group.”

Still, the move contains regulatory risks. Fifa, world football’s governing body, has rules against a single owner controlling clubs in the same competition. CFG’s initial strategy avoided this by expanding into countries where teams had little chance of facing each other on a regular basis. But if Girona, currently 12th in La Liga, were to become more successful, it could meet Manchester City in European competitions.

Patrick Vieira, a former Arsenal player, now coaches New York City FC © AFP

CFG has gained encouragement from a ruling from the Court of Arbitration for Sport this year, which found that RB Leipzig and Red Bull Salzburg could both compete in the Champions League this season, as their parent group did not exert “decisive influence” on the teams holding its name.

Patrick Vieira, the New York City coach, insists CFG “plays by the rules and regulations”. He says: “Think about Real Madrid and Barcelona, in England all the clubs have a lot of money. This is a different way of working, by people who are more creative than other people. It is one of the smartest moves taken in football in the past 20 years.”

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2017. All rights reserved.